It’s not often that popular science books focus on

bioacoustics. Recent notable examples include Don Kroodmsa’s The Singing Life of Birds and Birdsong of the Seasons, both of which

receive rave reviews from readers and, as is obvious from the titles, focus on

the amazing diversity of sounds produced by our feathered friends. But birds

are only one of many acoustically communicating species, and animals in general

are only one source of sound on our planet. Others include abiotic

environmental sources such as wind, waves, and geological activity, and, as has

been receiving much attention recently in the scientific literature, noises

that can ultimately be traced back to humans.

As most regular Anthrophysis readers already know, noise—or,

to be more precise, “unwanted sound”—is a serious problem in most contemporary

habitats, where it can disrupt sleep patterns, act as a distraction, cause

stress leading to other physical and emotional problems, and obscure the

acoustic signals of acoustically communicating species. The history of noise,

and all its pernicious effects, was recently cataloged by Hillel Schwartz in

the book Making Noise: From Babel to the

Big Bang and Beyond.

|

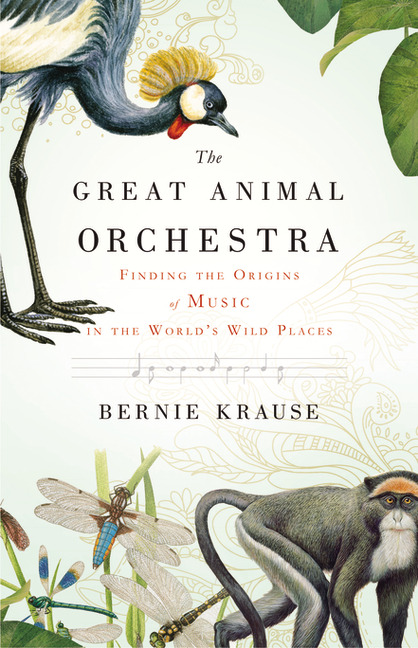

| Cover of the American version of the book |

But what about more pleasant cacophonies, such as the

explosion of sound that emanates from a rainforest as dozens of species of birds, insects,

amphibians, and mammals all vocalize simultaneously? What about the sound of a

crashing thunderstorm as its rain pummels leaves in the tree canopy and its

winds cause the branches to creak? These natural symphonies are the subject of

a new book released this week to US audiences: Bernie Krause’s The Great Animal Orchestra: Finding the

Origins of Music in the World’s Wild Places (available to UK readers in

April).

Krause’s book fills the gap between Kroodsma’s and

Schwwartz’s, examining the sorts of complex, multi-taxa sounds that do more

than simply provide ambience, but are not so overbearing that most of us would

classify them as “noise.” Rather, these acoustic stimuli are, Krause argues, the

origins of human music. After all, emerging in an era with no televisions,

radios, or stereos, our first musically inclined ancestors had only one source

of inspiration other than their own voices: the world around them. Thanks to

the huge variety of sounds in their environment—each differing in pitch, amplitude,

tempo, and timing of production—these early humans were by no means at a loss

for acoustic stimulation.

| Cover of the British version of the book |

The Great Animal

Orchestra covers a quite a bit of ground for a book that is only ~250 pages

long. The author, a former professional musician and Hollywood sound

expert, frequently describes his own experiences with nature’s music and his

growing interest in “soundscapes,” or complete collections of sounds that

characterize a given habitat. Over the course of a lifetime, Krause has

collected an audio archive comprising tens of thousands of samples, which

cumulatively could play for about 1,500 hours straight (or two solid months).

His personal acoustic journey serves almost as a parallel to that of the

average reader making his/her way through the book—beginning as a relative

novice to the world of biotic sounds and gradually becoming acquainted with the

richness of natural soundscapes. The reader first learns about the sources of

noise in the environment, and how they fit together to make “the great animal

orchestra,” and then is shown how this acoustic display is a vital part of the

human experience. Almost inevitably, the final chapters of the book deal with

habitat loss, declining biodiversity, and noise pollution—the factors that,

along with our own apathy, threaten to render many soundscapes extinct.

Although Krause does not shy away from scientific

explanations of relevant topics—how sound propagates, what makes an octave, how

to read a sonogram—he makes them accessible to lay readers while avoiding a

level of simplicity that would bore a fellow bioacoustician. Throughout,

Krause’s enthusiasm and wonderment are infectious. Some of the best passages

are those in which Krause describes acoustic scenes he has experienced over the

years—as in the following passage about Arctic glaciers:

The ice mass shatters as it is compressed

under great pressure and undergoes periods of melting and snow accumulation,

and in addition to the startling popping and groaning of the ice and the

ever-present wind and frequent storms, calving glaciers release huge walls of

frozen water into the shorelines of rivers, fjords, and seacoasts with a

volatile, thunderous burst of sound, the fallen accumulation generating huge

waves in the water below. Then there is the sound of the glacier’s own

movement: a slight, ominous oscillation caused by its relentless progression

overland—a slow, creeping sensation more felt than heard.

|

| Dr. Bernie Krause |

I have to admit that, while I found every bit of the book

fascinating, I did not always understand the logic behind its organization.

Some themes were revisited multiple times in a way that seemed scattered rather

than purposeful; several sections could have been better rooted in the central

theme—which, for that matter, could have been more clearly delineated and

reinforced throughout. Altogether, I feel that the book suffers from an

identity crisis that is never quite resolved; it is part autobiography (of an

unarguably interesting person), part history of music, part explanation of

bioacoustics, and part E.O. Wilson-style argument for the need for

conservation. There is no fundamental reason why all of these disparate topics

should not exist in one place; they are

complementary, as the book does make clear. My main complaint is that these

ideas never quite meshed into a single flowing narrative. However, I should

stress that these critiques reflect my own artistic preferences for a certain

style of organization, and do not have any bearing on the worthiness of the

ideas discussed here, since these are certainly worth the cost of the book and

the time required to read it.

Indeed, the bioacoustician, nature-lover, and

conservationist in me all concur that The

Great Animal Orchestra is a wonderful introduction to the wild world of

sound and the amazing things you can hear if you stop to listen. I agree with

Krause that the world is a richer place when you are aware of its acoustic

textures. Like the author, I find it unbearable to think that we are on the

cusp of forever losing certain sounds from our acoustic experience. Thanks to

habitat fragmentation and other anthropogenic influences, I may never again

hear bobwhites or whip-poor-wills calling behind my childhood home, and I am

acutely aware of how their loss alters the feel of the habitat. Similar losses,

often at much larger scales and involving many more species simultaneously, are

occurring around the world. Krause’s book is an elegant explanation of how

these losses threaten to mute the “great animal orchestra,” why each of us

should care, and what we can do to both enjoy the soundscapes that remain, and

attempt to preserve them for future generations.

---

To watch a Magic of Science episode with Dr. Bernie Krause, click here.The US hardcover edition of the book, published by Little, Brown and Company, is 288 pages long and is available at Amazon.com from 19 March 2012.

The UK hardcover edition of the book, published by Profile Books, is also 288 pages long and is available at Amazon.co.uk from 1 April 2012.

No comments:

Post a Comment